|

TYPHOON COBRA AND CARRIER TASK FORCE 38AN UNCOMMON ENCOUNTER DECEMBER 17-18, 1944By Carl M. Berntsen, SoM1/C INTRODUCTION

Snippets of information were abundant but the chapter "Typhoon Cobra and the Third Fleet" of Morison’ "History of US Naval Operations in World War II" provided most of the detailed information contained in this record. entitled "Typhoon Cobra and Third Fleet". I can express my own actions and reactions to the tempest outside from within a tightly closed up ship, but I had little knowledge of events taking place on the other 100 warships of the fleet. This record of Typhoon Cobra goes far beyond my personal knowledge of the storm. Drawing on other source materials I gained a deeper appreciation of the forces involved when we confronted nature head-on. "Cobra", by the way, is not an official name for the December 1944 Typhoon. Hurricanes and Typhoons were not given names at that time.

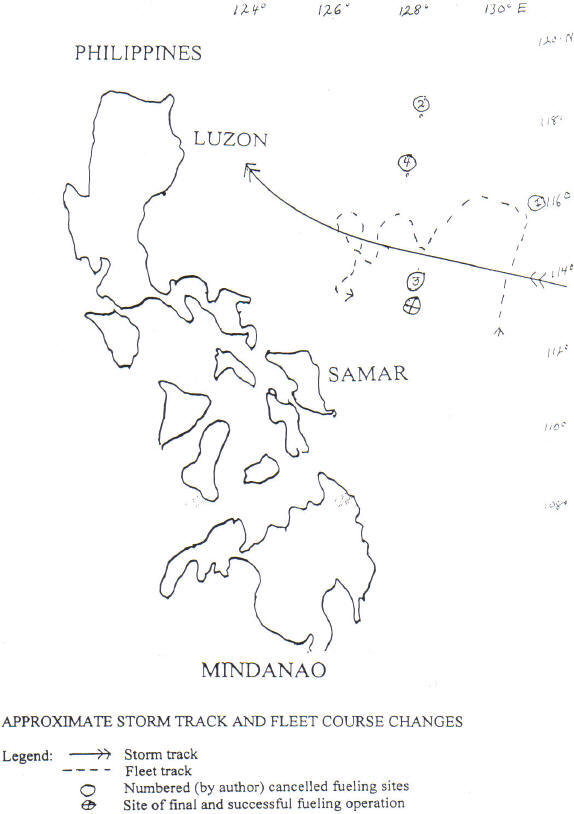

A battered DeHaven after a long time at sea The Carrier Task Force # 38 was the major element of the Third Fleet under the Command of Admiral Halsey. It was a massive assembly of warships. This Task Force consisted of three eight-mile diameter circles of ships in formation. Seventeen destroyers formed the outer ring. Inside the outer ring were two or three battleships and three or four cruisers. Inside that ring were 3 or 4 aircraft carriers—one or two of the Essex 35,000-ton class, and two converted cruiser or merchant ship hulls called light or escort carriers. All told, Task Force 38 was made up of about 90 warships. The number of warships is an estimate because at times Task Force 38 incorporated 4 or 5 groups including one British Group. The light or escort carriers operated with 28 to 30 aircraft, and had a top speed of 20 knots. The Essex-class carriers accommodated 90 to 100 aircraft and had a top speed of 30 knots. The DD 727 was one of the 51 destroyers in this Task Force. The DD 727 was the Flagship of Des Ron (Destroyer Squadron) 61. All ships in this Task Force had to maintain the same course, which changed at random times. The zigzag course was used when the Task Force was working in waters patrolled by Japanese submarines. Task Force 38 had been underway for three weeks, and had just completed three intensive strikes on Luzon. Admiral Halsey wanted to continue operations at sea for a while longer, so a rendezvous with the supply fleet was planned to replenish fuel and all other items necessary to sustain an extended attack. The replenishing fleet consisted of 35 ships—twelve fleet oilers, 3 fleet tugs, 5 destroyers, ten destroyer escorts, and 5 escort carriers. The replenishing operation started on the morning of December 17, 1944. Destroyers are usually first to be fueled because of their relatively limited operational range. They can be fueled from carriers as well as from the oilers in the replenishing fleet. Winds of 20 to 30 knots made the fueling operation difficult. The fueling site of 14 degrees 50’ N, 129 degrees 57’ E was selected as the nearest spot to Luzon outside Japanese fighter-plane radius. The Task Force aerological (meteorological) service gave no hint of any severe weather in the hours ahead. This lack of information was attributed to the fast pace of the task force into near-enemy-held areas, which made it impossible to establish advanced weather reporting stations. The weather service did the best it could. Most aircraft weather reports were at least 12 hours old before they reached the ships in the operating area. The Pacific Fleet Weather Central at Pearl Harbor sent weather forecasts twice daily to the Task Force by radio. Aboard the flagship New Jersey (BB-62) was Commander G. F. Kosco, a graduate of the aerology (meteorology) curriculum at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But, none of these resources were able to predict what was about to happen. Part of this dilemma was due to the nature of the pending storm. It was a small "tropical disturbance" that suddenly and unpredictably grew into a typhoon. All morning the seas were building up. The increasing wind and mounting waves made it difficult to continue fueling. The DeHaven (DD-727) was fortunate to be one of the early destroyers fueled. The Maddox (DD-731), a sister ship to the DeHaven (DD-727), was able to take on only 7093 gallons from the oiler Manatee (AO-58). The hose then parted and she had to cut the hawser to avoid a collision. Two hoses parted on the New Jersey (BB-62) while fueling destroyers Hunt (DD-674) and Spence (DD-512). The seas were getting rougher—winds were approaching 40 Knots. The escort carrier Kwajalein (CVE-98), one of the ships of the replenishing fleet, was unable to transfer pilots by breeches buoy. The ships crew turned to securing what were supposed to be replacement aircraft to the deck, and letting air out of the tires. The Fleet escort carriers were unable to recover two Combat Air Patrol aircraft. They were flagged off from their respective flattops and the pilots were ordered to turn their planes upside down and bail out. They were rescued by a destroyer. At 1300 Admiral Halsey ordered every ship to delay fueling and steam northwesterly to fueling rendezvous No. 2 (numbering of fueling sites added by author) at 17 degrees N, 128 degrees E. in hopes of resuming fueling at 0600 the next day. Admiral Halsey made this decision based on Commander Kosco’s assumption that the storm center (no evidence of a typhoon yet) was 450 miles SE of the Task Force’s position. It was later determined that the storm center was only 120 miles south of the Task Force. Admiral Halsey was reluctant to abandon fueling (the alternative was to RTB, Ulithi Atoll) because he urgently needed all ships fueled to support the Mindoro and Lingayen Gulf operations and other strikes on Luzon two days later. On Admiral Halsey’s orders, Vice Admiral McCain ordered Task Force 38, (all l00 warships and 80 replenishing ships) to set course 290-degrees for the 0600 rendezvous. But, he ordered destroyers Spence (DD-512) and Hickox (DD-673) to remain with the oilers and refuel at first opportunity. The Maddox (DD-731) was also low on fuel. By mid-afternoon , Captain Acuff, Commander of the replenishing group agreed that the storm was indeed a typhoon. And that the fueling rendezvous No. 2 set by Admiral Halsey would be directly in the typhoon track.

That evening there was an ominous glow in the sky. Spindrift from the crests of the ever-building waves coated the decks and hindered visibility. On a northerly heading the 727’s bow would ride on the crest of 30-foot waves, plunge down into the trough, burying its bow deep into the oncoming wave. The ship’s buoyancy struggled to rise to the surface, and as it did the entire ship’s hull shuddered as it shed the "thousand tons" of seawater off its decks. After hours of this head-to-head challenge with the sea one might begin to wonder how long the ship could take it. Probably the crew and Officers in the pilothouse experienced mild panic as they watched each wave slam up against the forward wall of the super structure. But generally the "inside" crew, while utilizing every handhold available, was handling the situation in good order. Maybe the experience during the shakedown cruise off Bermuda prior to our departure to the Pacific conditioned us somewhat for this occasion.

All ships in the Fleet were now experiencing extremely stressful conditions. The carrier Kwajalein (CVE-98) was experiencing the same beating as the 727. As each wave rolled under, the entire bow would come out of the water, hover for a few seconds, then crash down, taking the flight deck to the bottom of the trough. Seawater was flowing with every pitch and roll on the hanger deck. Zigzagging was cancelled after sunset—sonar was ineffective in seas like this, and submarines were not likely to operate in these conditions. The Admirals concern about the ever-worsening storm hastened his decision to abandon plans for the N0.2 rendezvous for fueling. And instead established a No.3 position at 14 degrees N, 127 degrees, 30’E. The fleet immediately changed course to 270. However this course ran parallel with the typhoon instead of at a wide angle from it. Several hours after the last course change the Admiral realized the fleet could not reach the No 3 fueling site on time. He then set a new site, No. 4, at 15 degrees, 30’ N, 127 degrees 40’E. At 2300 hours that evening Admiral Halsey ordered the fleet to change course from due West to due South at midnight in the hope of finding smoother water, and to NW at 0200 hours the next day for a fueling rendezvous. As luck would have it this move took a large part of the fleet directly into the path of the typhoon. At 0430 hours Admiral Halsey communicated with Admiral McCain on the Yorktown (CV-10) and Admiral Bogan on the Lexington (CV-16) asking for their appraisal of the storm situation. Their collective wisdom prompted the Admiral to cancel the No. 4 rendezvous (he did not set another) and to head due South at a speed of 15 knots , and commence fueling at random if and when possible. (the replenishing fleet was still within the area). However, it was soon learned that the seas were so rough that fueling was impossible. And worse, unbeknownst to the Admiral, this course again put the fleet on a collision course with the typhoon. At 0800 hours the Captain of the Nehenta Bay (CVE-74) of the replenishment group requested permission to leave formation with the light carriers Kwajalein (CVE-98) and Rudyerd Bay (CVE-81) and their escorts, owing to the pounding they were taking. Permission was granted but the course that he took in search of a better sea condition led him very close to the eye of the typhoon. By 0830 hours conditions were so bad the Admiral Halsey had to give up his "unnumbered" fueling rendezvous, and ordered all ships that could do so to continue on course 180—still assuming this would lead the fleet away from the storm center. At 0913 hours the course was changed to 220. At 1000 hours the barometer started falling noticeably, and the wind was backing counterclockwise. By 1400 hours the wind had risen to 73 knots. As the center approached the eye passed so near several carriers as to show clearly on their radar screens. Photographs made of Wasp (CV-18)’s radar screen of the eye have the appearance of surrealistic pyramidal shapes. Near the eye the wind gusts were over 100 knots. At 1150 hours Admiral Halsey, on board the New Jersey (BB-62) near the fringe of the storm ordered the fleet to steer 120 degrees. Good decision, this would take the fleet away from the center with the wind on the port quarter. But by that time the ships were strung out over some 2500 square miles of ocean and it was too late for some to escape. The typhoon reached its greatest violence between 1100 and 1400 hours December 18. Winds of 122 mph with gusts up to 150 mph were reported by ships close to the center of the storm. Admiral Halsey informed Fleet Weather Central of typhoon conditions. He was unaware at that time that three destroyers had already gone down. By the afternoon of December 18, Task Force 38 and its attendant replenishment groups were scattered over a space of 50 by 60 miles. All semblance of formation was lost. Several ships were fighting for their own survival, hardly any two were in visual contact, some lay DIW (dead in the water), rolling in the trough of the sea, aircraft were crashing and burning on the light carriers. From the pilot houses of battle ships and carriers it was reported that the weather was so "thick and dirty" that the sea and sky fused into one watery element. Occasionally a break would occur, and one could see escort carriers rising up on their stern, or their bow plunging under an oncoming mountain of water, and some destroyers rolling uncontrollably in arcs of 100 degrees. Serious damage was sustained by the Miami (CL-89), the Monterey (CVL-26), the Cowpens (CVL-25), the San Jacinto (CVL-30), the Cape Esperance (CVE-88), the Altamaha (CVE-18), the Aylwin (DD-355), the Dewey (DD-349), and the Hickox (DD-673). Less damage was sustained by at least 19 other vessels. The big carriers lost no planes, but the Hancock (CV-19), whose flight deck was 57 feet above waterline scooped up "green water" on the flight deck. The battleships were undamaged except for some topside "cleaning" of unsecured gear. Light carriers had a difficult time. Rolling and pitching caused plane lashings on hangar decks to part, planes went adrift, collided and burst into flames. The Monterey (CVL-26) caught fire and lost steerage. The fire was brought under control, but she lost 18 aircraft and sustained serious damage to 16 others. The Cowpens (CVL-25) lost 7 aircraft. The San Jacinto (CVL-30) reported that one unsecured aircraft on the hanger deck wrecked seven others. Four other light carriers lost 89 aircraft, but otherwise suffered only minor damage. Total aircraft losses including those blown overboard or jettisoned from the battleships and cruisers, numbered 146. Destroyers had the worst experience. Immediately after the Hull (DD-350) received an ordered course change to 140 degrees the wind speed increased to over 100 knots. The Hull (DD-350)'s fuel tanks were 70% full so she did not take on any salt-water ballast. That was an oversight. Almost immediately the Hull (DD-350) "lay in irons" in the trough of the sea with the north wind on her port beam, yawing between 80 and 100 degrees. The whaleboat, depth charges and almost everything else on deck were swept off as she rolled 50 degrees to the lee of the wind. The roll increased to 70 degrees. Then a gust estimated at 110 knots pinned her down. The sea flooded the pilothouse and poured down the stacks, and a few minutes later she went down. In Court Inquiry it was suggested that if the Hull (DD-350) had taken on sea water ballast in the 30% empty fuel tanks she would have been able to recover from the 70-degree roll and would have weathered the storm. The destroyer Dewey (DD-349), like the Hull (DD-350), got herself "in irons" broadside to wind in the trough of the sea—rolling heavily to starboard and unable to steer any course that would take her out of the trough. The Dewey (DD-349)'s fuel tanks were 75% full. The Captain ordered all topside weighty objects jettisoned, and took on 40,000 gallons of salt water as ballast--all of which was contained on the weather side. This maneuver allowed the ship to turn into the seas at a 35-degree angle and to gain steerage control. There was more to come. At 1210 hours the Dewey (DD-349) rolled 60 degrees to starboard, recovered, rolled 75 degrees and hung there. By now the barometer went off the scale at 27! Captain Mercer was about to order cutting off the forward mast to lower the center of gravity and reduce the "sail" effect. Then a wave slammed on to the side of the ship and the stack buckled at the boat-deck level and fell across the beam, completely flattened. Although some water entered the engine room, it reduced the "sail" effect so that stability was improved. By 1300 the storm had abated and the Dewey (DD-349) was able to maneuver around to a safe westerly course. Destroyer Aylwin (DD-355) also got away with taking on a seawater ballast. Passing close to the eye at 1100 hours she lost steering, engines stopped, and she rolled 70 degrees to port. Then she lay down on her side to port for 20 minutes. Barometer reading had dropped to 28.55. The engine rooms were abandoned when temperature reached 180 degrees, owing to failure of blowers. A Lieutenant and Machinist’s Mate, not being able to bear the heat any longer, crawled out on deck through the only escape hatch. They were overcome by the sudden change of temperature and collapsed, and were immediately washed overboard. At 1745 hours the Aylwin (DD-355) was underway at 7 knots, with water sloshing around her deck plates, but she managed to control the flooding by nightfall. The Hickox (DD-673), after six unsuccessful attempts to fuel on the 17th was down to 322 tons, 14 percent of her fuel capacity. Her CO began taking on sea-water ballast at 1750 hours. Over a 16- hour period she was able to take on only 246 tons of seawater. Unable to turn one way or another, the Commander decided to ride it out with minimal steerage and set "Condition Affirm"—all buttoned up. At 1130 hours on the 18th, the bridge lost steering. The steering-engine compartment took on water so fast that the sailors who tried hand steering had to be pulled out to save their lives. An all out bucket-brigade effort was made, working in darkness with water and oil sloshing over the men in heavy rolls . The temperature and humidity rose to such a point that it was impossible for the men to remain more than a few minutes without relief. The bucket brigade made some headway, freeing up some crew to rig up a submersible pump using the switchboard power supply on the No. 5 gun. Despite frequent clogging of the submersible pump with seamen’s clothing flooded compartments, but were almost clear by 1745 hours. Hand steering resumed and the worst of the typhoon had passed. The Hickox (DD-673) then complied with Admiral Halsey’s earlier order to the fleet, to "come to a comfortable southerly course in search of "fueling" weather". The Monaghan (DD-354), of the Farragut-class destroyer was one of the three destroyers that failed to stay afloat. The Captain reported to the Group Captain at 0925 hours, December 18 that he was unable to steer the ordered course, and was heading 330 degrees with the wind on the starboard bow. This course took the ship close to the typhoon’s eye. At 1100 hours an attempt was made to ballast her weather side, but it was too late. The overheads in the engine and fire rooms fractured and began to tear loose from the bulkheads. She made several rolls to starboard, hung there momentarily, then foundered. The Spence (DD-512), of the Fletcher class, formed a part of Task Group 38-3. Her fuel was down to 15 percent on December 17. After unsuccessful attempts to fuel from the New Jersey (BB-62), she was sent to another task group in hopes of fueling at the earliest opportunity. She had only enough fuel for 24 hours at 8 knots. About mid-morning, December 18, water ballasting was attempted, but too late. At 1100 hours the Spence (DD-512) took a deep roll to port, hung there a moment, recovered, rolled again, and then went down. RESCUES AND CASUALTIES"Cobra" moved on quickly during the night, and the morning of December 19 skies were clear with brisk winds. Admiral Halsey gave an amazing order! "All ships of the Task Force line up side-by-side at about ½ mile spacing and comb the 2800-square mile area" (in which the fleet had wandered in the past two days). From the upper deck of the DeHaven I saw the line of ships disappear over the horizon to starboard and to port. A concomitant search and rescue effort, unbeknownst to Admiral Halsey, was underway by Destroyer Escort Tabberer (DE 418), a unit of the replenishing fleet. The Tabberer (DE 418) was heavily damaged topside, and lost communication with the fleet. By chance a PIW (person in water) was sighted which lead to several more sightings and rescues. Communications were restored and rescue results reported to Admiral Halsey. At day’s end 92 men were rescued. Seven hundred and eighty perished. RECOLLECTIONS OF THE AUTHORDuring the night of December 19, the fleet, once again in formation of 4 circular groups, steamed toward the advanced base of Ulithi Atoll in the Carolina Islands. One of the heavy carriers had trouble keeping up speed with the fleet and proceeded to back down to the rear of it’s group to determine what the problem was. But its backing-down course was on a collision course with a battle ship. All ships in the fleet were on a zigzag course. The battleship refused to move. The carrier had only minimal maneuverability. Admiral Halsey got on the inter-ship radio and transmitted this message. "SWEAT BAND, SWEAT BAND, THIS IS RIP TIDE, RIP TIDE, REMEMBER THE SEASON, LET THE SPIRIT PREVAIL. OUT". The "OUT" meant "communication response not needed or requested". This message and reaction was profound. The view on radar showed the battleship veering to port to allow the carrier to proceed backing down to the outer ring of the group. The fleet proceeded to the advanced base of Ulithi Atoll at 15 knots. The bulk of the fleet arrived on December 24, Christmas Eve. Once anchored and secured, each ship was visited by a mail-delivery vessel, the deck of which held a mountain of Christmas mail. COURT OF INQUIRY SUMMARYAccording to this Court the destroyers Hull (DD-350), Monaghan (DD-354) and Spence (DD-512) maneuvered too long in an endeavor to keep station, which prevented them from concentrating early enough on saving their ships. But, the records of the Third Fleet as a whole indicated that little effort was made to keep station after 0800 hours December 18. Captain S. H. Ingersoll of carrier Monterey (CVL-26) was asked whether he felt free to drop out of formation and handle his ship any way he saw fit. He replied that he did. It was the urgent need of these destroyers for fuel that got them in trouble. Although Admiral Halsey should have made no attempt to fuel at 0600 hours on the 18th, he had no means of knowing where the center of the typhoon was, or even that it was a typhoon, until around 0900 hours that same day. Admiral Nimitz, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, presented a six-page document (confidential at that time) to members of the Court. Some of his remarks were critical, but always with the touch of an understanding Commander. But, he drove home this statement. "Steps must be taken to insure that commanding officers of all vessels, particularly destroyers and smaller craft, are fully aware of the stability characteristics of their ships;, that adequate security measures regarding water-tight integrity are enforced; and that effect upon stability of free liquid surfaces is thoroughly understood". The Admiral named several official naval documents of which each ships Commander should have been familiar. His final reference was to authors Knight and Bowditch, "—whose knowledge on the subject is exactly as true during this war as it was in time of peace or before the days of radio". Knight and Bowditch authored "The American Practical Navigator" in 1984, upgraded from Bowditch’s original of 1802. REFERENCESAdamson, Hans and George Kosco, Halsey’s Typhoons, Crown Publications. 1967 Calhoun, Raymond, Typhoon; The Other Enemy. Annapolis, the Naval Institute Press, 1981 Department of Navy, Typhoon, Navy Historical Center, Washington D. C. Department of the Navy, Extract from Report of Task Group 38.1, 14 June 1945, Naval Historical Center, Wash. D. C. Morison, Samuel, History of U. S. Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. 12 Leyte, Champaign, University of Illinois Press. 1958 National Weather Service, Weather Bureau Warning Service, Miami, Florida, 1943 Nimitz, Chester, Admiral, Commander in Chief, US Pacific Fleet, Pacific Fleet Confidential Letter, 13 February l945 Oppenheimer, David, Lieut. (jg), Navy Day with the Victory Fleet, Summary of DeHaven’s WWII Record, 27 Oct. 1945 Sheets, Robert, and Jack Williams, Hurricane Watch! Forecasting the Deadliest Storms on Earth, Vintage Books Division, Random House, 2001 The History Channel, Halsey’s Typhoons, VHS Documentary, AAE-42959 Tobin, Richard, A Memorandum to All Hands, USS Tabberer, DE 418 USA Today, Pacific Typhoons Batter U. S. Navy, 1944

PROPOSED FUELLING RENDEZVOUS AND

COURSE CHANGES

|

| Copyright © 1997-2023 USS DeHaven Sailors Association 2606 Jefferson Avenue, Joplin MO 64804 Contact Us |

After all these years I decided to record certain

events of shipboard experiences during the War of the Pacific. I was not

long into making notes and outlines before I realized that I was hard

pressed to feel confident in dates and details of the major events. I have

no problem remembering ravages of the typhoons we encountered, but what

typhoon was it in which the carrier Hornet’s forward flight deck was

smashed down and she steamed backwards into the wind to resume aircraft

takeoffs. And, which of the two atolls, Eniwetok or Ulithi was the most

advanced (closest to the enemy) base for the fleet. So, to research these

and other vague elements in my memory I resorted to the internet.

After all these years I decided to record certain

events of shipboard experiences during the War of the Pacific. I was not

long into making notes and outlines before I realized that I was hard

pressed to feel confident in dates and details of the major events. I have

no problem remembering ravages of the typhoons we encountered, but what

typhoon was it in which the carrier Hornet’s forward flight deck was

smashed down and she steamed backwards into the wind to resume aircraft

takeoffs. And, which of the two atolls, Eniwetok or Ulithi was the most

advanced (closest to the enemy) base for the fleet. So, to research these

and other vague elements in my memory I resorted to the internet.